At dawn, Vilma Trujillo was led out of the Celestial Vision church - a dark wooden cabin where she had been held captive for almost a week - and tied to a guava tree.

The 25-year-old had been taken there after starting to hallucinate and talk to herself. It was for her own good, she was told. Prayers were the antidote to the demons that possessed her.

“She was saying strange things,” remembers her aunt, Angela García.

The family knew she needed help, but they also knew it would take the best part of a day to reach a doctor from the scattering of poor homesteads in the rainforest of north-eastern Nicaragua, that is known as El Cortezal.

Instead, they sent for the young pastor from the evangelical church that Vilma had recently joined.

Twenty-three-year-old Juan Rocha said he could help.

He and his followers led her for an hour along muddy paths to the Celestial Vision church, at a lonely spot on a hillside.

Though Vilma had gone willingly, at a certain point she rebelled, grabbing a machete and swinging it through the air in a failed attempt to break free.

On the sixth night, one of the congregation professed to have had a divine revelation: God had sent a message that the demons could be expelled through flames.

Juan Rocha began to direct the proceedings, helped by about a dozen believers.

Some began to build a pyre, others went off to fetch more wood. It was at this point that Vilma was moved outside and tied to the guava tree beside the fire pit.

To this day, it is unclear if she was pushed into the fire, or if it grew and engulfed her, but soon the flames were clawing at her skin.

“I’m going to die, I’m going to die!” she cried out, according to her 15-year-old sister, who was inside the church praying when she heard the screams.

Paralysed with shock, the teenager listened to her elders exclaim that Vilma would soon be resurrected, free from torment.

Hours passed before one member of the group broke ranks and told the sister to run for help.

You won’t find El Cortezal on Google Maps, or even most local maps.

In the depths of the countryside - where in places virgin forest is still being burned to create arable land - there are no roads, no electricity, no phone lines, no police, no doctors, not even a shop.

It took me 10 hours to get there from the nearest town, Rosita - two hours by 4x4 truck, four hours on foot and four hours on a mule. The mobile phone signal is almost non-existent, confined to isolated patches of higher ground.

So the only place for Vilma’s sister to get help was at her aunt’s homestead. She ran along the overgrown paths, arriving out of breath and barely able to speak. She said simply: “They have burnt her.”

A rescue party headed by Vilma’s father, Catalino López Trujillo, arrived at the scene at midday, as the last flames were still flickering. López Trujillo found his daughter lying naked on the ground, with burns covering 80% of her body. Barely conscious, she asked him for water.

He and his nephew carried her back to Angela’s house. There Vilma was still able to reassure her tearful five-year-old son. “Los pastorcitos me bautizaron,” she told him. The little pastors baptised me.

López Trujillo gathered various siblings, cousins and uncles to create a makeshift stretcher from a hammock and two poles.

Before dawn the next day, they set off, carrying her for 12 hours overland, wading through rivers and struggling not to slip on the steep muddy paths through the rainforest.

When they finally reached Rosita, the doctors realised her injuries were too serious to be treated locally.

She was taken to an airport about 30km (20 miles) away and flown to the capital, Managua, but it was too late.

Vilma Trujillo died on 28 February from pulmonary oedema, her lungs filling with blood, and multiple organ failure.

Timeline

February 2017

15 - Vilma Trujillo is taken to the Celestial Vision church

21 - Fire is lit at 05:00, her father finds her at midday

22 - Vilma is carried from El Cortezal to Rosita

23 - She is flown to Managua

28 - Vilma dies in hospital

Nicaragua has plenty of violent crime, but this so-called “exorcism" shocked the nation.

In the immediate aftermath the media descended on Rosita, a town that forms part of the so-called mining triangle, where fortune-hunters have dug for gold since the late 1800s.

Television footage captured the stunned pastor, looking younger than his 23 years in a baseball cap and pink shirt, sitting in the back of a pick-up truck, being grilled by a combative journalist.

“Why did you burn her?” asks the reporter, before the accused is taken away by police.

“No, no,” he insists. “The spirit lifted her up, she fell into the fire.”

As he bats away one allegation after another, there is a revealing interruption.

One of his collaborators - his brother-in-law, Franklin Jarquín - looks into the camera with an ice-cold stare and blurts out: “She had committed an error. She had a life partner and she committed a mistake with another man.”

Juan Rocha, his brother Pedro José, his sister Tomasa and her husband Franklin Jarquín were all charged with kidnapping and murder.

So was a fifth participant - the one who claimed to have had a “revelation” about using fire - Esneyda Orozco.

When the case went to trial in Managua, those who attended said they saw no signs of remorse from the accused, all in their 20s.

El Cortezal was torn apart by the crime.

Vilma’s partner - who was away at the time of her murder - has since gone to live elsewhere, taking their two-year-old daughter with him.

Her first son - by a previous partner who left her - is living with her brother.

Orozco, who was three months pregnant during the trial, is raising a baby in prison.

Angela says she was told her house would be burnt down if she testified at the trial, and perhaps not surprisingly some of the family’s witness statements seemed guarded, as if they were trying to protect one of the accused.

One Nicaraguan told me: “Death threats around here aren’t just words.”

Vilma's father, Catalino López Trujillo, and Angela García at a court hearing

“There was a big commotion,” says Angela, with a voice that gently sings even the heaviest words.

For her own safety, she went to stay in San Miguel de Casa de Alto, more than 100km (60 miles) away, where the family is originally from and where Vilma is buried.

“We had to leave our crops, which were ruined,” she says. “We didn’t have anything to eat.”

The proud matriarch is back in her own home now, but as the anniversary of the death approaches, she says the tensions remain.

A suspicious armed man was hanging around her house a week before we met, she tells me, reawakening her sense of unease.

Only Vilma and her youngest sister had joined the evangelical church, the rest of the family remaining Catholic.

Angela said the girls wanted a fresh start, maybe some new hope, after their mother died of cancer in her 40s.

Vilma had thrown herself into the meetings and sang in the choir.

The young pastor was only a local farmer’s son, but he had completed a few years of schooling and to the mostly illiterate people of El Cortezal he seemed qualified to head the church.

When Angela speaks of Vilma, she smiles fondly.

“Ohh, she was so friendly, so helpful. Everyone always says a person was good after they die, but it’s true.”

Vilma lived in a house next door, where she used to make sweets, fresh cheese and bread to sell. “She worked twice as hard as most,” says Angela.

No-one will ever know now what was disturbing Vilma a week before she died.

There have been rumours, which can never be proven, including one that she was drugged and raped by a powerful local man. This is what led the church group to make accusations of extramarital sex - blurring the difference between rape and adultery.

I ask Angela if she can confirm this rumour, but she cannot. “I’ve heard that, but she never spoke to me about it,” she says.

Angela García

The teenage sister will not speak about what happened on the night of the so-called exorcism. “I don’t ask her about it,” Angela says. “She doesn’t want to talk.”

The young son, who saw his injured mother return, also remains silent on the subject. But Angela insists that they are both well.

Miuriel Gutiérrez, who works for a women’s rights organisation in Rosita, the nearest town, is not so sure.

She worries particularly about the sister, with whom she spent time in the days immediately after the murder.

Miuriel Gutiérrez

“She was in a state of shock. The image that stuck with her, and kept replaying, was that of her sister being burnt alive,” she says.

“We have spoken a few times on the phone since then. She says she is fine, but she won’t go back to church.”

News coverage of the case was extensive. Updates regularly made the front pages and nightly TV news.

Police press conferences were broadcast on Facebook Live.

When news site El 19 Digital wrote a round-up of the “shameful events that marked Nicaraguan history in 2017”, Vilma’s death featured prominently.

“Nicaraguans were alarmed and bewildered by what happened. They felt the pain of the victim and of her children,” it wrote.

In that article, and in most local press coverage, Vilma’s death was referred to not just as a murder case but as “femicide” - a word that, in the macho societies of Latin America, means more than the murder of a woman or girl.

“Femicide is a hate crime,” says Magaly Quintana emphatically, after stubbing out her cigarette.

Magaly Quintana

“It means when you are killed because you are a woman. Maybe by a partner. Maybe after being raped or violently attacked beforehand…”

Quintana is a veteran women’s rights campaigner, who co-founded a group called Catholics for the Right to Decide when, 12 years ago, abortion became fully illegal in the country - even in cases of rape or when the mother’s life is in danger.

These days the organisation also campaigns against gender violence. When I visit in December, Magaly is just finishing a newsletter, a sombre end-of-year round-up of femicides.

Catholics for the Right to Decide counted 51 in 2017, including Vilma’s.

“Using the word ‘femicide’ makes the problem visible,” Magaly says. “It highlights inequality in a society where men decide how you live and die.”

The term was coined by US-based feminist Diana Russell in the 1970s, as she strove to highlight the long history of gender-motivated deaths, from witch-burning and honour killings to the death of abused women from sexually transmitted diseases and botched abortions.

However the term really took off after a wave of violence against women in the Mexican city of Ciudad Juárez in the 1990s.

All across Latin America and the Caribbean, there has been a move to get femicide (femicidio or feminicidio in Spanish) listed in law as a specific crime.

Eighteen countries in the region, including Nicaragua, have bowed to the pressure in recent years.

While I have been in Managua, another case has occurred: a 20-year-old woman, allegedly killed by her security-guard boyfriend outside a shopping mall. Witnesses said he blew on the gun barrel triumphantly after shooting her six times.

The government immediately said it would look into restricting gun rights for security employees, but Quintana thinks it’s not weapons but a mindset that is driving the problem: the idea that men own women’s bodies, and can dispose of them when they don’t do what the man wants.

So was Vilma’s murder a case of femicide?

Technically no, because under Nicaraguan law femicide can only be committed by someone the victim has had intimate relations with.

And crucially, they point out, Vilma was punished for having sex outside marriage.

In societies where machismo culture is ingrained, not only are double standards applied to men and women when it comes to adultery, women may be blamed even when they are raped.

Rosita’s main street is lined with hardware shops, mini-marts and bars where you can leave your gun in a locker as you sing karaoke.

Taxis and motorbikes zip around the potholes, and ice-cream vendors on bicycles ding their bells for trade.

The office is spartan, with public health posters lining the walls offering information or advice on HIV, teenage pregnancy, and gender violence.

“I am a woman and I have rights,” reads one, in Spanish and a local indigenous language.

This is the women’s rights group run by Miuriel Gutiérrez and two other single mothers - her own mother and Brenda Miguel, a representative of the indigenous Mayangna community.

Half the battle in fighting gender violence is getting the community on side, Gutiérrez says.

She mentions a recent case where a husband attacked his wife with a machete for refusing to have sex. She was rehabilitated and can now walk, “more or less”.

Gutiérrez considers this a success story because neighbours chased after the culprit when they heard the screams and agreed to testify against him in court, as a result of which he was jailed.

“We are not going to end violence against women if people don’t recognise this as violence,” she says. “People see it as normal - a way to discipline women when they misbehave.”

One of the ways Gutiérrez tries to change mentalities is via her twice-weekly show on a community radio station, Radio Uraccan.

In the hour-long broadcast, she takes phone calls on a range of taboo subjects, including abortion, LGBT rights and sex work.

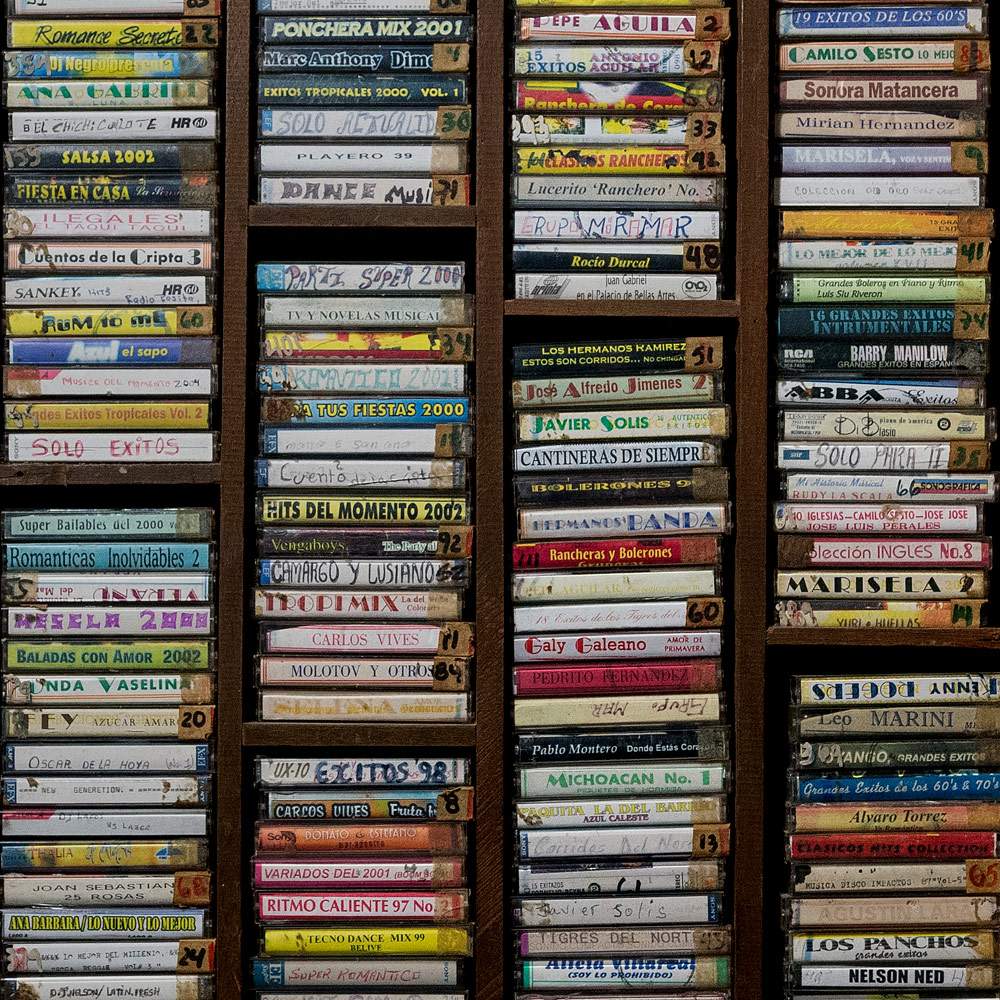

She takes me to the studio, where shelves are lined with old cassette tapes, with labels such as Tropical Hits, Love Ballads and Reggae Mania.

“I prefer to play Nicaraguan feminist music,” she says, introducing me to the work of singer-songwriter Gaby Baca, whose lyrics shift between celebrating female friendship and condemning street harassment.

Gutiérrez used her programmes to share news of Vilma’s death and the trial, and when she asked listeners about the sentencing, reaction was mixed.

Over the last year she has travelled back to El Cortezal a number of times to visit Vilma’s relatives and offer support.

She says the murder has had a profound effect on the surrounding communities.

“People started saying, ‘Be careful. Don’t let what happened to Vilma happen to you,’” she says.

“We are more alert about how religion is practised now.”

The superintendent of the Assemblies of God in Nicaragua, Rafael Arista, answers the phone with a weary note in his voice, making it clear that he would rather not be talking about Vilma Trujillo yet again.

He is trying to be amenable, but he exhales deeply as soon as I ask him about Juan Rocha, the pastor of the Celestial Vision church in El Cortezal.

Rafael Arista

“Unfortunately it was the press that started using the word ‘pastor’,” he sighs. “We didn’t have a single pastor of that name. It was the journalists who started calling him a pastor, and that was because they were trying to sully the name of the Assemblies of God.”

Rocha was more of a lay preacher than a pastor, he goes on, and the Celestial Vision church, while it was part of the Assemblies of God, was “not what we would call an organised church”. He would define it more as a “potential” future church.

He is losing patience with my questioning, even though I have barely started.

“In over 100 years nothing like this has happened before,” he snaps. “Why don’t you mention the good things we do, like building houses and running schools for the deaf?”

The Assemblies of God does, indeed, have many such projects. I have seen one of those schools for deaf children in Managua, located next to the Assemblies of God offices and the campus of Martin Lutero University, which the church also funds.

Founded in the US state of Arkansas in 1914, the Assemblies of God now has members in almost every country - 67 million of them in all.

In Nicaragua it has more than 600,000 members - 10% of the population. Its operations and charity work are funded by the faithful, who are encouraged to give 10% of their income to the church.

Angela García says even Vilma used to give the pastor a percentage of the money she made from selling sweets.

The church is vehemently opposed to extramarital sex, homosexuality and abortion.

“Perhaps no other area of sinfulness has brought such devastation and decay to our world,” it says on its US website, about sex outside a heterosexual, monogamous, lifelong marriage.

Meanwhile, those who identify as Catholic have shrunk from highs of 90% to around 50% of the population, according to the Pew Research Center.

As I talk with Pastor Arista, the official line on Vilma Trujillo’s case is clear: Juan Rocha is not a real pastor and the Assemblies of God does not practise violent exorcisms.

And yet beyond that, the message is unexpected. Every time I ask about Vilma and her family, Arista expresses sympathy for the perpetrators, whom he visits in prison. First he says their sentences are too long, then he suggests they could be innocent.

“In my opinion, this young person might have thrown herself into the fire,” he says. “Because I don’t believe that five people who are praying are going to all agree to throw someone into a fire.”

Much of our hour-long interview is taken up with his diatribe against the media, which he accuses of exaggerating the more lurid aspects of the case.

He says more attention should be paid towards the children of the five young convicted parents.

“It is very clear that there are a lot people who are not interested in suffering children, in children who are dying of hunger. All the news is interested in is a dead woman and, unfortunately, that’s the past.”

By the end of our conversation, Arista tells me there is sufficient evidence to show “that crazy woman” did it to herself. He does not elaborate, but no such evidence was produced in court.

I put down the phone feeling baffled. I didn’t expect him to take personal responsibility for what happened, but even after the outcry that followed Vilma’s death, he seemed tone deaf to how a lot of the country feels.

Every time I offered him a chance to express sympathy with Vilma and her family, I met a brick wall. And to hear her described as “a dead woman” and “that crazy woman” was startling.

After Vilma died, angry protesters pelted the church of the Assemblies of God in Rosita with rocks and the pastor here, Saba Calderón Tobares, seems slightly more in touch with popular sentiment.

Saba Calderón Tobares

He does accept that the prisoners committed the crime - “How did not one of them step back and say, ‘This is not right’?” he asks.

He also concedes that Vilma is likely to have been mentally ill, rather than controlled by the devil, and that there was no need for an exorcism.

It’s not clear which of these pastors - Arista or Tobares - is more representative of the church as a whole, though Rafael Arista’s predecessor as superintendent, Saturnino Cerrato, struck a hardline note when questioned on national television.

There was no doubt, he said, that the case was one of demonic possession.

“The devil exists. Demons exist,” he said, declaring them responsible for many of society's problems.

For psychiatrist José Miguel Salmerón, who has followed the Vilma Trujillo case closely, this is an instance of what he calls “a dangerous understanding of the world that dates back to the Middle Ages”.

He says that though no-one can diagnose Vilma posthumously, her symptoms - including talking about the devil - are common in hospitals for mentally ill people.

“The majority of the Nicaraguan population is not interested in mental health. People prefer supernatural explanations,” he says.

“The key to change is more education in schools. More biology and life sciences. We need to create space for critical reasoning and secular thinking. We need to separate religion from our interpretations of the world around us.”

Nicaragua’s feminists and the church - both its Catholic and evangelical branches - have long been at loggerheads.

The church scored a victory when, in 2006, abortion was made illegal in all circumstances.

Then six years later, women’s rights campaigners had their turn to celebrate after the passing of a law on gender violence, known as Law 779.

This put the crime of femicide on the statute books, and prohibited police from trying to mediate between a man and a wife, when the wife complained of domestic violence, rather than launching a criminal investigation.

Campaigners saw this as a form of pressure on the woman to stay with an abusive partner, leaving the man without even a police record.

The church, on the other hand, saw it as a way of preventing family break-up, and mounted a vigorous counter-campaign to get mediation reinstated. One Catholic bishop even declared that “the new number of the beast is not 666, but 779”.

Again, the church was successful: mediation was reinstated for first-time and minor offences.

In 2014 came a further setback for women’s rights campaigners. President Daniel Ortega issued a decree widening the role of community groups in resolving domestic disputes - making it even more difficult for women to press criminal charges.

Overall the message seemed clear: deal with it or get your community to deal with it.

The country’s Sandinista government has become increasingly religious since its revolutionary days.

Together they operate under the slogan “Christian, Socialist, Solidarity”, though some critics see this as a transparent ploy to win religious votes.

After Vilma’s murder, though, the Nicaraguan parliament swung into action and passed a law more favourable to feminists than the church. It introduced a new offence of causing death “by religious fundamentalism”, punishable by 25 to 30 years in prison.

Women’s rights campaigners mostly regard this as an empty gesture. But there are others, even some in the church, who see it as a step in the right direction.

“Religious freedom cannot override basic human rights,” says Berman Bans, a Capuchin friar in the southern Caribbean municipality of El Rama.

Bans says he sees the damaging effects of fundamentalism clearly in his own parish - specifically a tendency to blame the devil for everything from drug abuse to homosexuality.

“Vilma’s story seems like an isolated case, but there is a fertile context behind it all - socially, economically, culturally,” he says.

El Cortezal’s pastor, Juan Rocha, had only studied up to grade four (the same as a typical child or nine or 10), according to his father, but it was enough to earn him local respect.

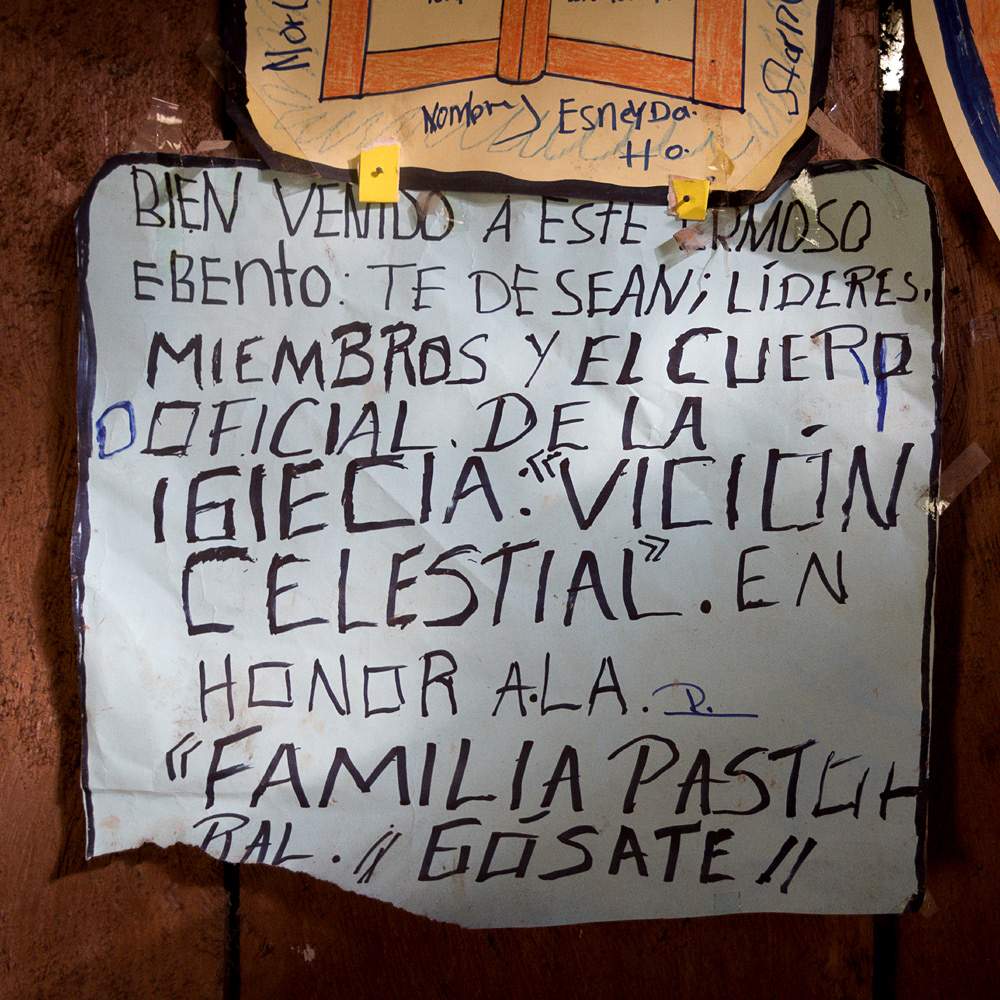

Some of the misspelt mottos that can be seen on the wall of the church may have been written by him, others were more clearly by members of his devoted congregation.

“I am the good shepherd; I know my sheep and my sheep know me,” reads one, in a rough scrawl.

Vilma could also read and write. She had reached third grade at school but left when she first became pregnant in her teens.

In Bans’ view, it is hard to separate the interwoven factors that led to her death: the lack of education, the toleration of violence against women, the abuse of power by religious leaders, and stigma over mental health.

“It’s like a Russian doll.”

Miuriel Gutiérrez, though, sees some signs of hope. The neighbours who testified against the man who attacked his wife with a machete, for example. And recently there was another case with some similarities to Vilma’s, but with a very different ending.

“One day, a young boy had some sort of fit and he was forcibly taken out of hospital and to an evangelical church,” she tells me. A group of men held him down while women shouted that he was possessed.

“People thought, ‘Nooo, this can’t be happening again,’” Gutiérrez says.

A handful of them pursued the group, filming it all on their phones and calling the local press. The situation soon calmed down and the boy was taken back to his father, unharmed.

“It’s like a little light has been lit,” she says.

Magaly Quintana is not convinced that Vilma’s death has changed anything. “Every so often there is a big reaction to an extreme case,” she says, “but violent deaths aren’t ending.”

But Gutiérrez is more optimistic.

“You can't bring a woman back to life,” she says.

“But this case set a really important precedent in our country. Even with so many adverse conditions affecting women, there was an outcry, justice was done in court and there was a change in the law.

“There is a lot to do here, but that does not mean we cannot do it.”