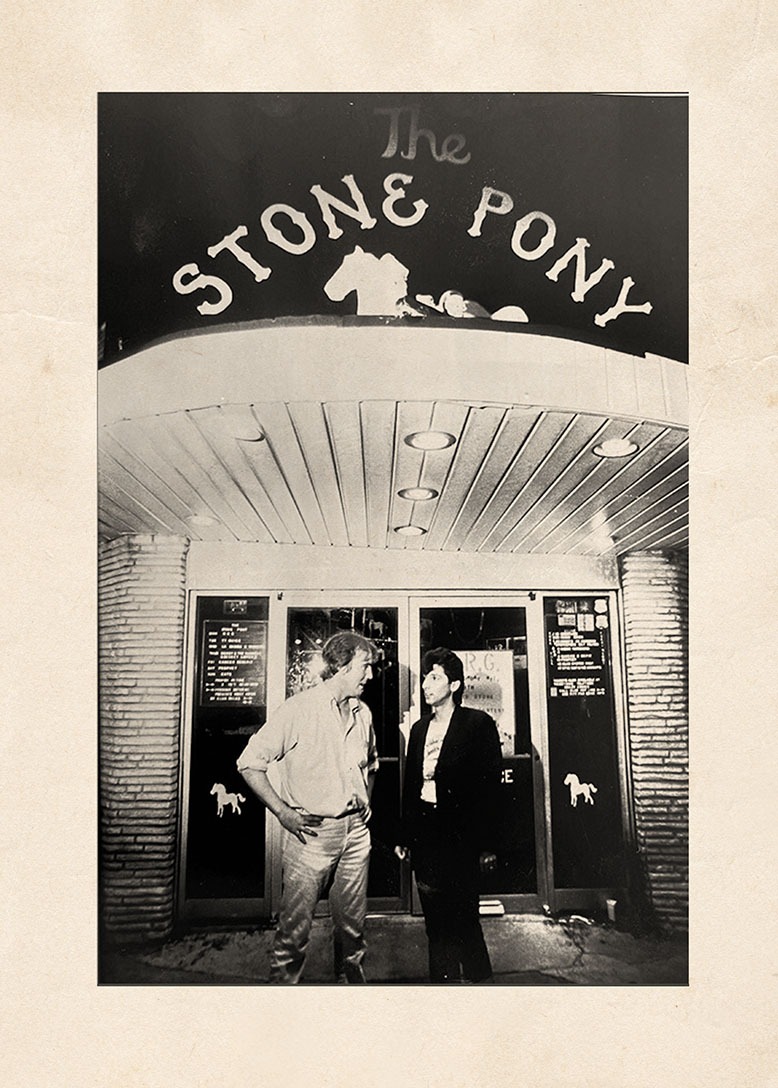

Musician Bobby Bandiera (right) ahead of his band’s 1985 benefit show, with Steve Mannion of Hazlet, vice president for Make-A-Wish, outside the Stone Pony. Photo: Asbury Park Press/USA Today Network/Jim Connolly

He never intended to open a rock club, let alone one of the most hallowed in music history.

It was late 1973, a quiet weekend at the Jersey Shore, and Jack Roig says he was just “killing time.”

A computer-programming consultant in Manhattan, Roig had worked many summer weekends on the floor of what he refers to as a “rambunctious” boardwalk bar in Point Pleasant called the Rip Tide. He harbored dreams of opening a small, unremarkable bar of his own, akin to the “gin mills” that dotted every block of his native Washington Heights neighborhood.

One thing Roig knew for certain: Asbury Park was off the table. The once-lively resort town was only a few years out from the 1970 race riots, spurred by post-segregation economic and social tensions. Residents had fled; businesses were boarded up. Springwood Avenue, on the city’s west side—previously home to a vibrant Black community and a rich jazz and blues culture—was in ruins. Although the east side of Asbury remained a refuge of sorts for a free-spirited community of young musicians—among them, Southside Johnny, Steven Van Zandt and Bruce Springsteen, who’d been luxuriating in a heady, jam-until-sunrise scene since the late ’60s—the town, on the whole, was still a shell of its former self, especially in the off-season.

Roig phoned a real estate agent about an ad he’d seen in the paper. “I told him, ‘I don’t want anything to do with Asbury,’” Roig, 82, recalls. “He said, ‘Well, I have a place I can show you up in Deal, but I just got this [other] listing. I don’t even have keys for it yet. You mind if we stop there? It’s on the way.’”

They never made it to Deal. Roig purchased the future Pony—then an abandoned disco called the Magic Touch—on the spot, without so much as stepping inside. “It was impulsive,” he says, recalling Asbury’s barren beachfront. “Not really a very good business decision.” (On the plus side, he points out, there was unlimited parking.)

The venue’s layout was conducive to a bar with a band—so “that’s what happened,” Roig says matter-of-factly. As for the name? “I woke up one morning with some young lady, and…she had little horses on her T-shirt, and something clicked,” he recounts.

Opening night at the Stone Pony on February 8, 1974—half a century ago this year—was bleak; portending, perhaps, the various storms the venue would weather over the next several decades. Snow piled on Asbury Park. The heat went out; the ice machines died. “Thank God it snowed,” Roig muses, “because the band couldn’t show up, and I didn’t have the money to pay ’em anyway.” Exactly one patron, an acquaintance, materialized and insisted on paying for his beer. The night’s take: $1.

Despite that ill-fated first evening, the Pony actually “did all right” until Labor Day, Roig says. He was running the venue with manager Butch Pielka, a former fellow bouncer from Point Pleasant’s recently shuttered Rip Tide, whose regulars began frequenting the Stone Pony. Locals still in Asbury, plus residents from nearby towns, followed suit. So did local bands, Roig says.

Once the summer waned, however, so did the customers. In December, part of the Pony’s roof ripped off during a nor’easter. Their insurance company went bankrupt. Foreclosure loomed.

It was around that time that the local Blackberry Booze Band, featuring future Asbury Jukes frontman Southside Johnny Lyon, began performing at the Pony. “We played the kind of music we wanted to play…so we got the worst nights,” Lyon says, recalling that a cover band, Colony, known for playing strictly Top 40 radio hits, held the Pony’s coveted weekend slots. But after a few slow Tuesdays, Thursdays and Sundays, the Blackberry Booze Band began attracting crowds. One snowy winter evening, the place was suddenly packed. “I think that’s when people started to realize that this was a real venue to see bands,” Lyon says. “And Bruce would come down to play….It became kind of a place for real musicians.”

The Blackberry Booze Band morphed into Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes, cofounded by soon-to-be E Street Band guitarist Steven Van Zandt, in 1975 (the same year Springsteen released Born to Run). The Jukes’ horn-heavy melding of rock ’n’ roll, soul, blues and R&B would become, for local fans and faraway listeners alike, a kind of sonic shorthand for the Pony—though Roig emphasizes that every band who played there, unique in its own way, “made the place.”

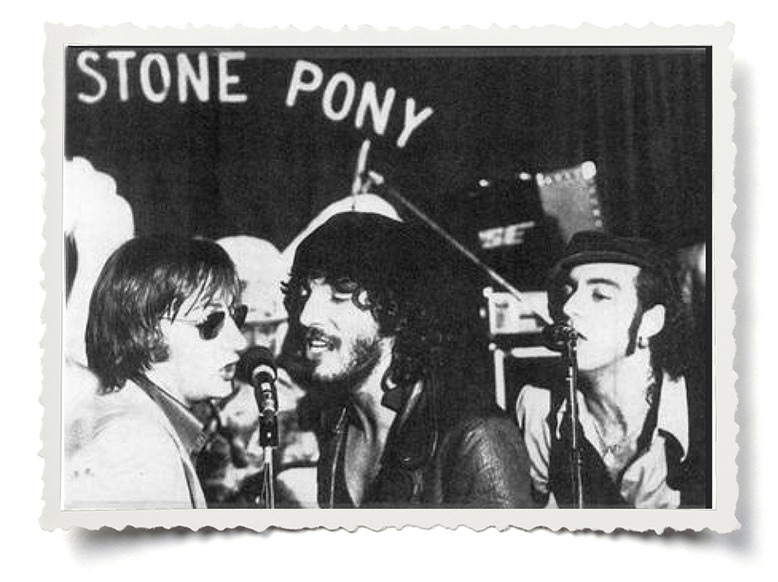

Southside Johnny Lyon, Bruce Springsteen and Steven Van Zandt perform at the Stone Pony during the Asbury Jukes’ famed radio-broadcast show on Memorial Day weekend in 1976. Photo: Asbury Park Press-USA Today Network

On Memorial Day weekend in 1976, a live national radio debut of the Jukes’ first album, I Don’t Want to Go Home—broadcast on nine stations, Lyon says—gave the rest of the country a taste of the sweaty spontaneity emanating from this little corner of the Jersey Shore. Springsteen showed up to perform. So did Ronnie Spector and Lee Dorsey. That night “really broke [the Pony] open,” Lyon says. “It became a famous club to play….Asbury Park became a small nexus for new bands, and it was very exciting.”

Pielka (who died in 2018) and Roig were “hardcore” guys, Lyon fondly recalls. “I used to get into arguments with them all the time about pay for the band, how much can you charge at the door…and I’m not a big guy, but I would take ’em on. Because I knew they needed me, and I knew I needed them.”

Throughout the ’70s and ’80s, an increasingly famous Springsteen continued to make frequent surprise appearances, imbuing the Pony with an unmistakably mythic quality. Groupies flocked there, hoping to glimpse him performing, dancing in the audience, or sneaking behind the bar to pour drinks. Tourists came by the busload. Letters addressed simply to “Bruce Springsteen, U.S.A.” arrived in the mail, Roig remembers.

Under this spotlight, the Pony began drawing national acts: Elvis Costello, the Ramones, Cyndi Lauper. But no amount of recognition could cushion the Pony from the city outside its dark doors, bogged down by rising crime and corruption, or from the financial and legal woes that would soon put an end to its first act. When the Pony shuttered in September 1991, it wouldn’t be the last time.

Deal businessman Steven Nasar reopened the Pony in 1992. He hired local concert promoter (and former Asbury Juke) Tony Pallagrosi to cater to a younger crowd amid a burgeoning punk-music movement. The New Brunswick-born Bouncing Souls opened for Green Day there in 1994. A tent in the adjacent lot for outdoor concerts was an early incarnation of the future Summer Stage scene. Still, Asbury continued to deteriorate through the ’90s, and Nasar closed the Pony in 1998—though not before turning it into a short-lived dance club, Vinyl, and painting it, to the horror of many locals, completely pink.

The venue sat untouched until 2000, when Jersey City entrepreneur Domenic Santana purchased it. He didn’t have personal ties to Asbury Park, but had scoped out the city as a potential investment site and been struck by a big group of tourists taking pictures outside the ghostly Pony. Santana brought in Eileen Chapman, an Asbury Park resident since the Pony’s 1974 opening and a stalwart supporter of the city and its music scene, as manager. (Chapman, now an Asbury Park councilwoman and director of the Bruce Springsteen Archives at Monmouth University, had previously managed Mrs. Jay’s, a beer garden next door to the Pony.) Santana renovated the space to return it to its original glory days, recreating lacquer tables and sourcing photos and memorabilia for the walls. Chapman provided a few personal items she’d saved. As they worked to revive the venue, Chapman often put herself in the shoes of the original owners. “I would just think about Jack and Butch….What would they be deciding?” she says. “Carrying on that legacy was really, really important to me. Making sure that everyone who used to come there felt comfortable coming back.”

In 2001, Chapman purchased the venue’s first outdoor stage, a major component of the Pony’s revitalization in recent years, from friend Carl “Tinker” West (and Springsteen’s first manager), with money her husband had given her to buy a new car. “After he got over his shock,” Chapman jokes, he ended up building the first outdoor bar to accompany the stage.

When developers initially approached Asbury Park with talk of taking over the waterfront, “it seemed they wanted to…create huge condominiums and apartment complexes, and really change what Asbury Park would look like,” Chapman recalls. “They were thinking more Miami. And we were thinking, We need to keep our music here.” She organized a Save the Stone Pony campaign—faxing musicians and record agents all over the world, creating signs, and leading a parade down Ocean Avenue. “It was absolutely important to keep the club there, and to create an entertainment district,” she says. “Opportunities for people to visit…for music to thrive, for musicians to have a place to hone their craft.”

The Pony’s current general manager, Caroline O’Toole, came on in 2003. Keeping the venue alive as Asbury Park continued to struggle was not for the faint of heart. Times were often “very dark,” she says, and the Pony’s future remained “unsecure.” Her first Memorial Day, she recalls, “there was not a soul in sight.” The tide turned dramatically in 2008, when corporate developer Madison Marquette purchased the Pony and began putting millions into revitalizing Asbury, transforming it into the city we know now.

Asbury Park native FLETCHER performs at the Stone Pony Summer Stage. Photo: David Zeck

These days, the Pony proudly honors its legendary rock ’n’ roll roots while booking broad, eclectic lineups—bands of all ages and genres, from Gaslight Anthem to Carly Rae Jepsen. There are disco nights and dance parties. Passionate crowds pack the intimate venue year-round and gather at the outdoor Summer Stage May through October. Shows this month include FLETCHER & FRIENDS (June 1–2) and the North to Shore Festival’s Asbury Park leg (June 10–16), featuring Gary Clark Jr., Band of Horses and others. “The Stone Pony represents this intersection of my hometown roots and this wild musical journey I’ve been on over the years,” says singer FLETCHER, 30, an Asbury Park native. “It’s a reminder of where I came from. You can never take the Jersey out of the girl.”

Echoes Chapman: “It feels like home….It’s a local place to gather.”

The day after E Street Band saxophonist Clarence “the Big Man” Clemons passed away in 2011, the Pony opened its doors as a sort of makeshift memorial site. “We knew people would just want to come and be together and remember him,” O’Toole says. At some point, the house DJ put on a live version of Springsteen’s “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out.” When the words “…and the Big Man joined the band” played, she says, “I swear: I have never felt an electricity like that in the room before. It was unbelievable. To this day, I’ve yet to experience it….It was a once-in-a-lifetime moment.”

[RELATED: E Street Band’s Jake Clemons Talks Stone Pony, Pre-Show Rituals and the Supernatural]

In 2015, Bleachers frontman Jack Antonoff launched his inaugural Shadow of the City music festival at the Summer Stage (this year’s is June 15). “I always wanted to have a place where [our audience] could be like, ‘OK, I’ll meet you there’…our place where we can all [reunite],” he told NJM earlier this year.

In 2018, rock photographer Danny Clinch cofounded Sea Hear Now, a beloved annual music, arts and surf festival on Asbury’s beach that draws some 35,000 fans (September 14-15 this year; Noah Kahan and Springsteen are headlining). Nick Corasaniti, a Jersey native and longtime Pony-goer, especially relishes Sea Hear Now’s Saturday-night super jams at the Pony, which stretch late and raucous into the early morning. “I wasn’t around in the ’70s, so I missed those epic, till-the-sun-rises, close-the-doors, stop-serving-the-alcohol-but-keep-the-music-going-until-the-band-can’t-go-any-longer [sessions],” he says. “I think the closest we get now are those Sea Hear Now super jams. All of them are magical.”

Corasaniti, a political correspondent for the New York Times, has authored an oral history of the Stone Pony, I Don’t Want to Go Home (out June 4 from HarperCollins), an engrossing, comprehensive chronicle of the venue’s ups and downs, told in the voices of the colorful characters closest to it. A book-release party at the Pony is slated for June 8.

This past winter, on the anniversary of the Pony’s 1974 opening, New Jersey officials proclaimed February 8 Stone Pony Day. “Not many businesses get something like that, you know?” O’Toole says. “Governor Murphy called me and congratulated me.…It just speaks volumes of what the Stone Pony means not only to Asbury Park and to the Jersey Shore, but to the state. It’s a landmark.” The Pony also hosted a panel that week with the team from the Springsteen Archives; local musicians, employees, community members and founding owner Roig shared memories.

“I’m proud of the people that I work with, and that we have been able to keep this legacy going for the next generation,” O’Toole says. “At the end of the day, it’s about the music.”

No one knows New Jersey like we do. Sign up for one of our free newsletters here. Want a print magazine mailed to you? Purchase an issue from our online store.