The FBI and Martin Luther King

Martin Luther King was never himself a Communist—far from it. But the FBI's wiretapping of King was precipitated by his association with Stanley Levison, a man with reported ties to the Communist Party. Newly available documents reveal what the FBI actually knew—the vast extent of Levison's Party activities

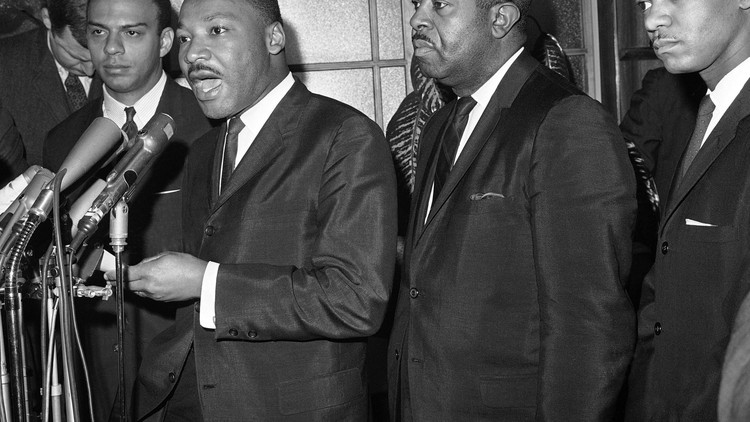

On October 10, 1963, U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy committed what is widely viewed as one of the most ignominious acts in modern American history: he authorized the Federal Bureau of Investigation to begin wiretapping the telephones of the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. Kennedy believed that one of King's closest advisers was a top-level member of the American Communist Party, and that King had repeatedly misled Administration officials about his ongoing close ties with the man. Kennedy acted reluctantly, and his order remained secret until May of 1968, just a few weeks after King's assassination and a few days before Kennedy's own. But the FBI onslaught against King that followed Kennedy's authorization remains notorious, and the stains on the reputations of everyone involved are indelible.

Yet at the time, neither Robert Kennedy nor anyone else outside the FBI knew more than a tiny part of the story that had led to that decision, or even the identities of the two FBI informants who had set the investigation in motion. Only in 1981 were their names—Jack and Morris Childs—publicly revealed, but even then the relevant documents were so heavily redacted that only the most bare-bones sketch of what had taken place was possible.

But now an ongoing FBI "reprocessing" of those documents, pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act, is resulting in the release of hundreds of largely unredacted pages that finally allow the story to be told.

The crucial figure was Stanley David Levison, a white New York lawyer and businessman who first met Martin Luther King in 1956, just as the young minister was being catapulted to national fame as a result of his role in the remarkable bus boycott against racially segregated seating in Montgomery, Alabama. The FBI knew, in copious firsthand detail from the Childs brothers, that Levison had secretly served as one of the top two financiers for the Communist Party USA in the years just before he met King. The Childs brothers' direct, personal contact with Levison from the mid-1940s to 1956 was sufficient to leave no doubt whatsoever that their reports about his role were accurate and truthful. Their proximity to Levison also gave them direct knowledge of his disappearance from CPUSA financial affairs in the years after 1956.

In the months immediately following Levison's visible departure from CPUSA activities, his selfless assistance to King soon established him as the young minister's most influential white counselor. But when the FBI tardily learned of Levison's closeness to King in early 1962, the Bureau understandably hypothesized that someone with Levison's secret (though thoroughly documented) record of invaluable service to the CPUSA might very well not have turned up at Martin Luther King's elbow by happenstance. With the FBI suggesting that Levison's seeming departure from the CPUSA was in all likelihood a ruse, Robert Kennedy and his aides felt they had little choice but to assume the worst and act as defensively as possible. The Kennedy Administration kept itself at arm's length from King, and events quickly spiraled, with the federal government undertaking extensive electronic surveillance of King himself.

The information that Jack and Morris Childs furnished the FBI, from 1952 to 1956, about their repeated face-to-face dealings with Stanley Levison concerning CPUSA finances establishes beyond any possible question that Levison in those years was a highly important Party operative. Given how richly detailed the Childs brothers' evidence about Levison actually was, the new and unredacted information merits an airing at some length.

The story began in late 1951 or early 1952, in New York, when two Bureau agents approached Jack Childs, a forty-four-year-old CPUSA veteran who until late 1948 had been a low-level functionary in the Party's highly secret financial apparatus. Jack's older brother Morris, a senior Party figure who previously had been the head of the CPUSA in Illinois, had been removed as editor of the Party newspaper, the Daily Worker, in mid-1947, ostensibly because of a serious heart condition. Then, in 1948, the CPUSA failed to provide medical support when one of Jack's young sons was stricken with a cancer that cost him an eye, and the brothers all but quit the Party.

One CPUSA veteran who observed their alienation was Patrick Toohey, who in the late 1930s had been the CPUSA's resident ambassador in Moscow. When Toohey began cooperating with the FBI, in the spring of 1950, Jack and Morris Childs were among the former colleagues whose experiences he recounted. The Bureau soon succeeded in adding Jack Childs to its stable of informants, and after an introduction from Jack, both Morris and Morris's companion, Sonia Schlossberg, followed suit.

Jack Childs had served as primary "leg man," or assistant, to William Weiner, the CPUSA's chief financier, from 1945 to 1948. In May of 1952 he recalled for agents how Weiner had garnered secret contributions and handled the Party's extensive cash repositories. Among the top contributors, Jack said, were Stanley and Roy Levison, twin brothers who owned a Ford dealership in northern New Jersey that contributed well over $10,000 a year to the CPUSA. "On three or four occasions after Weiner had received money from Stanley Levison, Weiner gave the money to Jack Childs who placed it in a safe deposit box in Childs' name" at a New York bank, an FBI memo detailing one of Jack's earliest debriefings recounted. What's more, when Jack stopped working for Weiner, in 1948, "he transferred to Stanley Levison all cash, bonds, and lists of depositories and records there[to]fore under the informant's control." Stanley Levison was a new name to the FBI.

The FBI's interest in the Childs brothers concerned the future far more than the past, and the Bureau wondered whether their long-standing friendship with Weiner could lead to their reactivation as Communist Party members. Morris, living in Chicago, expected a visit from Weiner in September of 1952, but late that month he informed his handler, Special Agent Carl Freyman, that another visitor from New York had been in touch with him a few days earlier: Stanley Levison. Levison "told the informant that he had been delegated by William Weiner of the National Office, Communist Party, to contact informant," and Levison "questioned him concerning reasons for his failure to keep in contact with the National Office of the Communist Party, and also concerning the informant's health." Morris's answers more than passed muster; Levison briefed him on a host of Party developments and stressed the importance of precautions to avoid FBI tails and surveillance. "Levison advised the informant that he spent one and one-half hours reaching the point where he contacted the informant." The painful irony of Stanley Levison's vetting Morris Childs for reactivation in the upper reaches of the CPUSA would start to become clear only a decade later.

Morris traveled to New York City for a ten-day visit late in November, and phoned Weiner upon his arrival. Weiner "greeted him warmly and suggested that CG 5824-S [Morris's FBI-informant code number] call Stanley Levison. NY 694-S [Jack's informant code number] advised that Weiner with Levison's assistance controls the financial operations of the CPUSA. As a result of a call to Levison [Morris] met Levison in front of NY Public Library," on Forty-second Street. A day or two later Morris met Weiner at Penn Station and went with him to Weiner's home, in Far Rockaway, Queens, where Morris spent the night. "Weiner was curious to know how [Morris] existed during the past four years and [Morris] gave him a plausible explanation which seemed to satisfy Weiner. [Morris] mentioned that [Jack] had been of considerable assistance to him financially." Weiner arranged for Morris to meet the CPUSA leader, William Z. Foster, for lunch a few days later, and Morris's rehabilitation appeared all but complete.

In late January of 1953 Harry I. Miller, of Chicago, a longtime Party activist whose business, the LaSalle Leather Company, was another big contributor to the CPUSA's secret accounts, visited New York. Jack Childs, who had helped to set LaSalle up as a Party business before handing off the connection to Levison in 1948, met Miller in the lobby of the Park Sheraton Hotel, at Seventh Avenue and Fifty-sixth Street, at 4:30 P.M. on January 24, as FBI agents watched. "Fisur ['physical surveillance'] revealed that at 5:35PM, 1/24/53, Miller was engaged in conversation with [Jack] in the lobby of the hotel." As Jack later related, Miller told him that "Levison gets about $200 per week out of the business for the CP," somewhat less than LaSalle's contribution back in 1948, and that he and Levison had also acquired a 50 percent interest in another firm, Liberty Luggage, on behalf of the Party.

Minutes after Jack and Miller parted in the lobby, Stanley Levison visited Miller's hotel room, where the FBI had planted a recording device. Among other subjects, according to an FBI paraphrasing of their conversation, Levison and Miller "discussed anti-Semitism in Russia and the satellite countries."

They stated that a couple of the Russian leaders had been accused of anti-Semitism, but that this was only a rumor. Stanley stated that he was a lawyer and that the evidence in the matter would not be admissible in any court. Stanley said that the trouble involved Jewish capitalists. Stanley said that Israel had moved over to the West and now was a real danger spot; that Zionism had become a major menace, and that Israel is now an enemy state—a Fascist state just like Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia had been. Stanley said that a year ago Israel pretended to have a foot in each camp.

A few moments later "Stanley said that the anti-Semitism situation was not as bad as the 'pact' (possibly the Hitler-Stalin Pact) which could not be discussed with people."

Morris Childs returned to New York in early May and again saw Levison; a few months later Levison told Jack that the Bureau had tried unsuccessfully to plant someone in Miller's Chicago office. But "bag jobs"—the Bureau's name for illegal late-night break-ins in which the victims' office files were photographed—gave agents many of the details they needed about Levison's and Miller's CP business operations. Cooperative bank officers, who made available all the records of their customers' financial transactions, supplied the rest. Levison was helping another Chicago Party veteran, Victor Ludwig, launch a lithographic printing venture called Sunset Plate, in Los Angeles, and Jack Childs eagerly pitched in. "When [Jack] reported the results of his operations in behalf of Levison to the latter, Levison was highly pleased and offered to compensate [Jack] in the amount of $200 for his services. [Jack] declined to accept the money for himself, suggesting that Levison give the money to the CP as a donation from [Jack]." Jack and Morris seemed like devoted Communists indeed.

Levison and Betty Gannett, a top CPUSA administrator, each told Jack and Morris that the Party was greatly worried about the liver cancer that was threatening to end William Weiner's life, and in mid-November of 1953 Jack reported that Weiner's aide, Lem Harris, expected that "the heaviest burden of Weiner's business enterprises probably will fall upon Stanley Levison" following Weiner's death. Jack was seeing Levison regularly, but with Weiner's end approaching, he also pressed Gannett to draw Morris into more top-level work, telling her that in his opinion "[Morris] is a better Communist today than he ever was, and his best work is ahead of him."

By early 1954 the Party was in desperate need of funds. The Childs brothers had long-standing ties to Canadian Communists, some of whom had known Morris since their joint training in Moscow, in the early 1930s. The Canadians might possibly open a crucial financial spigot. Then, on February 20, William Weiner died, and the following day Morris flew to New York and went with Jack immediately to the funeral home. Weiner's widow, Esther, was hysterically furious at the CPUSA's lack of interest during her husband's final days; as a result, an FBI memo summarizing Morris's experience recounts, "the informant and [Jack] then purchased a wreath and this was the first bouquet of flowers that appeared on the Weiner casket."

Esther Weiner told Morris that she felt she did have some friends, namely "the brothers (Stanley and Roy Levison) and you," but she also said that on the very day of her husband's death Stanley and his wife, Beatrice, had come to the Weiner home to remove many of "Willie's" financial documents. She asked Morris to see Levison in her behalf, to ask that Party financial support still come her way. "The informant met Levison at the Statler Hotel in New York and had lunch with Levison ... Levison during this conversation indicated that he had taken over most of the CP national financial responsibilities ... and indicated that he had assumed most of the responsibility for the 'big money financing' formerly held by Weiner."

Four weeks after Weiner's death Betty Gannett asked Jack to open the Canadian pipeline as soon as possible, because the CPUSA had a "desperate" need for $120,000. She asked that the Canadian Party "transmit through [Jack] 'as much cash as the Canadian CP can spare without affecting adversely its own immediate needs.'" Gannett told Jack "that responsibility for raising the $120,000 ... rests upon her and Stanley Levison, each being responsible for $60,000."

Following Weiner's death the FBI stepped up its surveillance of Levison, wiretapping his home telephone for the first time and arranging—with the "excellent" cooperation of a former Bureau agent employed by Chicago's Conrad Hilton Hotel—for the bugging of his room during a late April trip there. That cooperation further allowed for the photographing of Levison's papers and also those of his fellow guest Victor Ludwig. During one electronically preserved conversation Levison explained "the Party's success in infiltrating" the American Jewish Congress, in which Levison had become an officer for the West Side of Manhattan chapter. As a result, Levison said, the chapter was publicly criticizing the McCarran-Walter immigration law and the Red-baiting Senator Joseph McCarthy, of Wisconsin, in full accord with the CPUSA's political agenda. Levison said that he himself had given six anti-McCarran talks, and "he advised that he indirectly incorporated in these speeches the idea that the Eisenhower administration was rapidly advancing toward fascism."

When Harry Miller visited New York, in July, the FBI again rolled out its hotel-room tape recorders. A summary reported that at 11:15 P.M. on July 26, as Miller and Levison conversed, "Miller received a telephone call from [Morris], who was in the lobby of the Statler Hotel and Levison and Miller immediately left the room to join him 'for coffee.'" A few days later Morris advised the Bureau that the Party's National Finance Committee was now composed of Levison; Gannett; Isadore Wofsy, of New York; and Jack Kling, of Chicago.

In late November of 1954 Levison told Jack Childs that the Party would no longer invest in new businesses, for fear of their vulnerability to hostile government action. Instead the CPUSA would focus more than ever on recruiting or reactivating major donors, or "angels," who could make annual contributions of five or six figures.

At the end of 1954 a longtime Party operative named Phil Bart supplanted Kling and took overall charge of CPUSA financial matters. Morris passed along Esther Weiner's description of how Levison had taken her on a "very circuitous route" to meet Bart, and early in 1955 Jack recounted a similar story told to him by Lem Harris: "According to Harris he had been taken by Stanley and Roy Levison by a circuitous route to a secret rendezvous in NYC where he met Bart."

But just a few days later Jack reported a more intriguing piece of news related to him by a Party operative named Sam Brown, who had attempted to get in touch with the Levison brothers about prospective donors, only to be told "that hereafter, and for an indefinite period, the Levisons are 'out of circulation' and may not be contacted by their 'old friends.'" Jack wondered if this meant that they were engaged in "underground operations," but he obtained no definitive explanation. Meanwhile, the Party's financial crisis deepened. Bart told Jack two months later that the "Reserve Fund," the hoard of cash and bonds that Weiner had long overseen, had received no new income in the past year. Given that, "Bart said he should like to invest a part of the Reserve Fund in a 'sure-fire investment,' such as a business that would return a hundred percent profit without risk." Neither the Communist financiers nor the FBI agents busy monitoring their day-by-day conversations appear to have appreciated the irony of the CPUSA's hoping to build communism through free-market capitalism.

No improvement in contributions occurred during subsequent months, and Bart complained to Morris that "even the Levison boys have grown stale and are in a rut." But the FBI, on notice from its wiretaps that Levison was rendez-vousing in public places on an almost weekly basis with Isadore Wofsy, finally managed to witness one such encounter, at midday on June 24, 1955, in a subway corridor at Forty-second Street, just three blocks from Levison's office, on East Thirty-ninth Street. Forty minutes later the agents saw the two men inside the Woolworth's store across the street from Levison's office, "where [Levison] handed a white envelope to Wofsy." Four weeks later agents saw Levison and Wofsy meeting in the same subway corridor. "Levison and Wofsy engaged in a discussion at this location for about fifteen minutes and were observed to be making frequent references to papers which both held in their hands."

The FBI believed that Stanley Levison remained a major player in the CPUSA financial hierarchy, but neither a renewed wiretap on his home telephone nor a series of late-night bag jobs at his office produced any evidence to flesh out his encounters with Isadore Wofsy. The burglars were "unable to develop any information appearing to be connected with CP underground activity, or any new data appearing to be connected with current CP financial operations," a New York report to FBI headquarters about one mid-August break-in concluded.

But Jack's and Morris's information continued to attest to Levison's active involvement. In mid-September, Sam Brown told Jack that the Levison brothers were coming to his apartment one evening to discuss Party finances; in early December, Morris, in New York for a national Party conference, recounted how a Chicago Party member had informed him that "he obtained $500 for the Illinois-Indiana District from Stan Levison, and asked [Morris] to contact Levison before leaving New York City to obtain additional money for the Illinois-Indiana District from Levison." On December 8, FBI headquarters was told, Morris displayed to an agent "an envelope containing $700 which he had obtained on that date from Levison."

Similar reports persisted into 1956. On April 2 Jack told Bureau agents that Isadore Wofsy had come to his office at noon to ask him to "hold" $1,000 in cash, because Wofsy, who now bore the title of CPUSA treasurer, feared that he might be "picked up" by the IRS. "Wofsy indicated to the informant that the one thousand dollars was part of a collection of forty-five hundred dollars, which he had obtained earlier that day from Stanley Levison," a memo recounted.

Then, three weeks later, Jack told an FBI agent named Al Burlinson that Phil Bart had "completely relinquished control of CP National Office financial operations to Wofsy." Burlinson explained in a memo, "This change in the financial set-up is due to friction between Bart and the Levisons, Stanley and Roy, who have control of CP business enterprises. The Levisons will continue to operate the business they now control, but will not expand their activities any further. They will hereafter turn over the profits of the enterprises they control to Wofsy, and the latter will maintain regular contact with them."

In mid-June, Jack told agents that Wofsy was still meeting Levison at least weekly, probably because Levison was holding a large portion of the Reserve Fund's cash assets. The very next day Jack reported that Wofsy had come to him with $10,000 in cash and had requested that Jack change it into smaller bills; Wofsy told Jack that he had gotten the money earlier that day from "a guy on Park Avenue," and New York agents added, "It is believed the 'guy on Park Avenue' referred to Stanley Levison, who was observed meeting Wofsy on the morning of the above day by [New York Office] agents" in the same Forty-second Street subway corridor they had used so many times before.

At present the reprocessing and release of the Levison documents is stalled at the early fall of 1956, just a few weeks after a new bugging of Levison's office was added to the FBI's surveillance repertoire. But a combination of the heavily redacted documents released twenty years ago and some relatively cleaner ones processed two years ago (as part of the modest file on the civil-rights activist Ella J. Baker, a close colleague of Levison's in 1956-1957) makes clear that evidence of Levison's direct involvement in CPUSA financial affairs declined precipitously in late 1956 or very early 1957. In late March of 1957 the FBI dropped Levison from its list of "key figure" Communists, and on June 25 a redacted source—either Jack or Morris Childs—"advised that insofar as he has been able to determine, Stanley Levison and [redacted—no doubt Roy] are no longer involved in the CP Reserve Fund operation and have not been so involved since early 1957, or some time prior thereto. [redacted—Jack or Morris] stated that Stanley Levison is now a CP member with no official title, who performs his CP work through mass organization activity."

Stanley Levison was forty-four years old when he first met the twenty-seven-year-old Martin Luther King Jr., in 1956. Stanley and Roy had grown up in Far Rockaway; Stanley attended the University of Michigan before obtaining two law degrees from St. John's University, in Queens, in 1938 and 1939. Medically deferred from military service, he spent the war years managing New York tool-and-die firms—Unique Specialties Corporation and Colonial Tool and Machine—before buying the New Jersey Ford dealership in 1945 and then overseeing a host of import-export, property-management, and industrial-production companies whose overlapping relationships and countless financial transfers proved so complicated as to preclude any complete FBI analysis of Levison's little empire. Divorced from his first wife in 1942, after a three-year marriage, Levison soon remarried, and by the mid-1950s was the father of a young son.

When Ella Baker and her fellow African-American civil-rights activist Bayard Rustin introduced Levison to King, a special relationship quickly blossomed; from the late 1950s until King's death, in 1968, it was without a doubt King's closest friendship with a white person. In December of 1956 and January of 1957 Levison served as Rustin's primary sounding board as Rustin drew up the founding-agenda documents for what came to be called the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Like Rustin, Levison, and Baker, King and a network of his southern African-American ministerial colleagues hoped that the SCLC could leverage the success of the Montgomery bus boycott into a South-wide attack on segregation and racial discrimination.

By April of 1957 Levison, like Rustin, was counseling King about the first major national address that King would deliver—from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, on May 17. Over the ensuing months Levison negotiated a book contract for King's own account of the Montgomery boycott, Stride Toward Freedom, and then offered King line-by-line criticism and assistance in editing and polishing the book's text. Levison also took charge of other tasks, ranging from writing King's fundraising letters to preparing his tax returns.

King repeatedly offered Levison payment for his aid, but Levison firmly refused. He wrote King,

My skills were acquired not only in a cloistered academic environment, but also in the commercial jungle ... Although our culture approves, and even honors these practices, to me they were always abhorrent. Hence, I looked forward to the time when I could use these skills not for myself but for socially constructive ends. The liberation struggle is the most positive and rewarding area of work anyone could experience.

Those private comments to King may offer the best evidence available for fathoming the transition that Stanley Levison appears to have made during 1957.

Levison and King grew closer over the years, but neither of them could escape what Jack and Morris Childs had relayed to the FBI about Levison. The FBI approached Levison face-to-face in early 1960, asking if he would like to talk about what he knew, but Levison rebuffed the offer. Then, on January 4, 1962, Isadore Wofsy, with whom Levison apparently was still in direct touch, happened to tell Jack Childs that Levison had had a major hand in writing a speech that King had delivered to the AFL-CIO's annual national convention a month earlier. Just four days later Attorney General Kennedy received notice from the FBI director, J. Edgar Hoover, that Levison, identified as "a member of the Communist Party, USA, ... is allegedly a close advisor to the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr."

Kennedy and his aide Burke Marshall, the assistant attorney general for civil rights, regarded the FBI's information as both dependable and dangerous. They were told nothing of Jack or Morris except that the FBI's informants were very well placed. But the pressing questions were about Levison and King, not about the identity of the source. By early 1962 King was the leading symbol and spokesperson for the southern black freedom struggle. Levison, the FBI told Kennedy and Marshall, had recently installed as head of the SCLC's small New York office a young African-American man named Jack O'Dell, whose publicly documented record of affiliation with the CPUSA had drawn the attention of hostile congressional committees just a few years earlier. Kennedy's inner circle resolved that every Administration aide acquainted with King would warn him fervently but vaguely about the political danger of continuing his association with Levison and O'Dell. King politely accepted and then privately dismissed warning after warning.

Within weeks Kennedy had authorized the wiretapping of Levison's office; the FBI added a bug on its own authority. Neither source produced any evidence either of nefarious contacts or of a manipulative attitude toward King, but at the end of April, Levison found himself subpoenaed to appear before the segregationist James O. Eastland's Senate Internal Security Subcommittee. Levison testified under oath, "I am a loyal American and I am not now and never have been a member of the Communist Party," but he invoked the Fifth Amendment in response to all questions about the CPUSA and its financial affairs. To Levison's surprise, King's name was never raised at the committee session.

In mid-June the bug in Levison's office picked up his description of how he had recommended that King hire Jack O'Dell as his administrative assistant in Atlanta. Nothing had come of the idea, but for anyone who wanted to see an ulterior motive for Levison's commitment to King, the recommendation was suspect.

In late October of 1962 FBI leaks to friendly newspapers about O'Dell's presence at the SCLC resulted in news stories that led King to suggest falsely that O'Dell's employment was coming to an end. That evidence of King's tactical disingenuousness increased the disquiet within the Kennedy Justice Department; shortly thereafter the Attorney General approved a new FBI wiretap on Levison's home telephone.

But several months later, in March of 1963, when Jack Childs provided the FBI with ironclad evidence that Levison had explicitly severed whatever remaining ties he, Roy, and several old friends had still had with the CPUSA, the FBI conveyed that crucial news to absolutely no one outside the Bureau, not even the Attorney General. At a March 19 lunch with his old colleague Lem Harris, Levison said—as Harris recounted in a memo that Jack Childs passed on to the FBI—that "a whole group, formerly closely aligned with us, and over many years most generous and constant in their support," had now concluded that "the CP is 'irrelevant' and ineffective," and would supply no further support. The Harris memo was confirmed by what an FBI wiretap overheard Stanley telling Roy the very next day about his conversation with Harris: "I was tough, and I think I established my firm view, firm position."

Levison's break with the CPUSA was unknown to Burke Marshall, to Robert Kennedy, and to President John F. Kennedy when all three men reiterated to King in mid-June of 1963 that he must separate himself from Levison and O'Dell. Within days another leak to a newspaper revealing O'Dell's continued presence at the SCLC led King to announce O'Dell's resignation. Soon after that Levison himself, fully aware of the alarm that the Kennedys were voicing about him to King, told King that with Congress about to begin consideration of the Kennedys' landmark civil-rights bill, he and King had no choice but to put an end to direct contact with each other. "I induced him to break," Levison told the historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. in 1976. "The movement needed the Kennedys too much. I said it would not be in the interests of the movement to hold on to me if the Kennedys had doubts."

Yet King remained reluctant to lose Levison's assistance and counsel, and thus he detailed a mutual friend, the young African-American attorney Clarence B. Jones, of New York, to serve as a telephonic intermediary between himself and Levison. Marshall and Robert Kennedy picked up on the ruse almost immediately, and within days Kennedy had authorized the wiretapping of Jones's home and office. Kennedy considered adding a tap on King as well, but decided to hold off.

In early August of 1963 King happened to stay at Jones's home for several days, at which point both the FBI and, by extension, the Kennedys were introduced to a new aspect of King's life—namely, his sexual endeavors, which in subsequent months would all but replace Levison as the focus of the FBI's surveillance of King. But at that time Marshall and Robert Kennedy were far more worried by the extensive evidence of King and Levison's communication by way of Jones. The wiretap in Jones's office recorded King asking for advice from "our friend" and apologizing for not calling him directly: "I'm trying to wait until things cool off—until this civil rights debate is over—as long as they may be tapping these phones, you know—but you can discuss that with him." Several weeks later Robert Kennedy authorized the wiretapping of King's home telephone, in Atlanta; a wiretap on the SCLC office telephones followed a few days afterward.

The FBI's wiretaps on King's telephones remained in place until April of 1965 (at home) and June of 1966 (at the office); the wiretapping of Stanley Levison continued until several years after King's assassination, on April 4, 1968. Transcripts from the Levison tap attest to what a valuable, insightful, and influential friend Stanley Levison remained to King right up to King's death.

The transcripts from the wiretaps on King and his advisers also answer a question that came to preoccupy President Lyndon Johnson just as it had the Kennedy brothers and J. Edgar Hoover: Was Martin Luther King Jr. any kind of Communist sympathizer? Of course not—but the FBI never passed along to Johnson or to anyone else what King said to Bayard Rustin one day in early May of 1965, when the SCLC was tussling with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee over a public statement proclaiming movement unity: "There are things I wanted to say renouncing Communism in theory but they would not go along with it. We wanted to say that it was an alien philosophy contrary to us but they wouldn't go along with it." Instead the FBI continued to distribute utterly misleading reports that declared just the opposite; as one newly released CIA summary from just a few weeks before King's death asserts, "According to the FBI, Dr. King is regarded in Communist circles as 'a genuine Marxist-Leninist who is following the Marxist-Leninist line.'"

Stanley Levison died in September of 1979, without ever honestly acknowledging just how far his political journey had gone. Levison was never forthcoming about what he had been before 1957, just as the FBI was never forthcoming about what he no longer was after 1957. Levison died without ever learning that it was his old CPUSA comrades Jack and Morris Childs who had precipitated the FBI's surveillance of his friendship with King.

The Childs brothers went on to many other exploits in the years after they last saw Stanley Levison: they reopened the CPUSA's financial pipeline to Moscow, and at the FBI's behest they oversaw the delivery of millions of dollars from the Kremlin to the otherwise utterly moribund CPUSA. (To the FBI, the only thing better than no American Communist Party was a Communist Party effectively controlled by the Bureau.) Throughout the 1960s and 1970s Morris and Jack traveled the globe as the CPUSA's international ambassadors. In Moscow on November 22, 1963, Morris witnessed and attested to the utter shock and dismay of the Soviet Union's top leaders at the assassination of John F. Kennedy; after returning from a visit to Havana six months later, Jack passed along Fidel Castro's comments to him about the Kennedy assassination. Jack and Morris represented a huge intelligence coup. The firsthand information they provided to the FBI about Stanley Levison's secret financial work for the CPUSA in the years before Levison became Martin Luther King's most important political counselor changed American history in a profound way. If the Childs brothers had never signed on with the FBI, or if Jack had not heard about his old comrade Levison's newfound friendship with Martin Luther King, the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations would most likely have embraced both King and the entire southern black freedom struggle far more warmly than they did.